Fish use visual differences between divers to recognize the person who rewarded them

A new study by scientists from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behaviour (MPI-AB) in Germany has found that wild fish can recognise individual divers based on external visual cues such as different coloured wetsuits or fins.

Beyond the occasional anecdote, there is little scientific evidence that fish can recognise humans. A 2018 study found that archerfish bred in captivity were able to recognise computer-generated images of human faces in laboratory experiments, and octopuses have also been found to differentiate between individual humans – but both of these studies were based on experiences in unnatural, laboratory-based conditions.

‘Nobody has ever asked whether wild fish have the capacity, or indeed motivation, to recognize us when we enter their underwater world,’ said Maëlan Tomasek, a doctoral student at MPI-AB and the University of Clermont Auvergne, France, who led the study.

The fish that volunteered

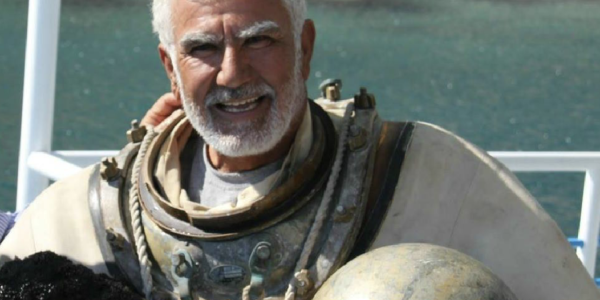

The research team conducted the study eight meters underwater at a research site in the Mediterranean Sea where populations of wild fish have become habituated to the presence of scientists.

Their experiments took place in open water and fish participated in trials as ‘willing volunteers who could come and go as they pleased,’ according to Katinka Soller, a bachelor student from MPI-AB and co-first author of the study.

To test if the fish could learn to follow an individual diver, Soller fed them while swimming a distance of 50m and wearing a bright red vest over her wetsuit. Once the fish had begun to follow her she repeated the experiment but without the vest, and kept the food hidden until they had swum the full 50m along with her.

From the dozens of fish species inhabiting the marine station, two species of seabream seemed particularly willing to engage with the experiment. Not only that, but the same individual fish began to show up to follow her.

‘Once I entered the water, it was a matter of seconds before I would see them swimming towards me, seemingly coming out of nowhere,’ said Soller, who even took to giving them names: ‘There was Bernie with two shiny silver scales on the back and Alfie who had a nip out of the tail fin,’ she said.

After 12 days of training, some 20 fish were reliably following Soller on training swims and she could recognize several of them from their physical traits. By identifying individual fish participating in the experiment, the team were able to run an experiment to test if the ‘named’ fish could tell Soller apart from another diver.

The two-diver test

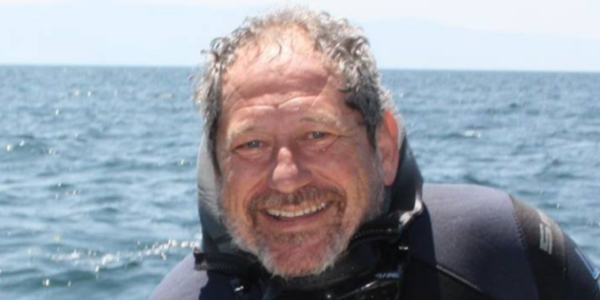

Soller and Tomasek dived together wearing dive gear that was slightly different in terms of style and colouring, such as the different sets of fins pictured below.

Both divers started at the same point but swam in different directions, but the fish followed both divers equally. ‘You could see them struggling to decide who to chase,’ said Soller.

Soller, however, fed the fish that followed her, whereas Tomasek did not. On the second day, the number of fish following Soller increased significantly – with four of six named individuals exhibiting strong positive learning curves during the experiment.

‘This is a cool result because it shows that fish were not simply following Katinka out of habit or because other fish were there,’ says Tomasek. ‘They were conscious of both divers, testing each one and learning that Katinka produced the reward at the end of the swim.’

When Soller and Tomasek repeated the trials wearing identical diving gear, the fish were unable to discriminate between the two of them, strong evidence that fish had associated the differences in the dive gear – most likely the colours – with the individual divers.

‘Almost all fish have colour vision, so it is not surprising that the sea bream learned to associate the correct diver based on patches of colour on the body,’ said Tomasek.

Association based on visual clues is something that humans, of course, do themselves – especially while diving in sub-optimal conditions or at night when we often have to rely on differences in equipment colour and fin style to recognise our buddies.

Also like humans, the authors say that – given enough time – the fish might have learned to pay attention to subtler human features to distinguish between the divers.

‘We already observed them approaching our faces and scrutinizing our bodies,’ said Soller. ‘It was like they were studying us, not the other way around.’

The study corroborates many anecdotal reports of animals recognising humans, but is unique in its approach to performing dedicated experiments with wild fish.

Finding that wild fish can quickly learn to use specific cues to recognize individual human divers, the scientists say it stands to reason that many other fish species – pets included – can recognise certain patterns to identify us, a foundation for special interactions between individuals, even across species.

‘It doesn’t come a shock to me that these animals, which navigate a complex world and interact with myriad different species every minute, can recognize humans based on visual cues,’ said Senior author Alex Jordan, who leads a group at MPI-AB.

‘I suppose the most surprising thing is that we would be surprised they can. It suggests we might underestimate the capacities of our underwater cousins.’

‘It might be strange to think about humans sharing a bond with an animal like a fish that sits so far from us on the evolutionary tree, that we don’t intuitively understand,’ said Tomasek, ‘but human-animal relationships can overcome millions of years of evolutionary distance if we bother to pay attention.

‘Now we know that they see us,’ he added, ‘it’s time for us to see them.’

This article is adapted from an article on the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior News homepage.

The post Wild fish can recognize individual divers appeared first on DIVE Magazine.