“Don’t poke the bombs.”

Eight divers titter as we settle into our liveaboard’s spacious interior salon, where briefings are augmented by maps and critter lists displayed on a big-screen TV. In capital letters topping the map of a Tulagi harbor site called Garbage Patch is written this admonition. A joke, right?

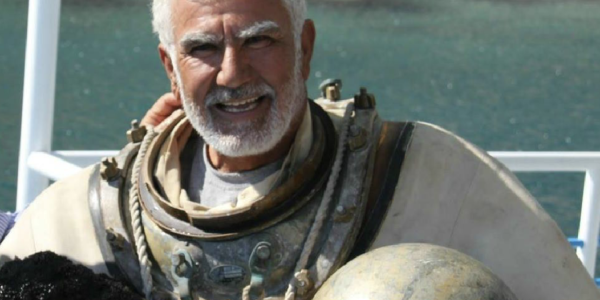

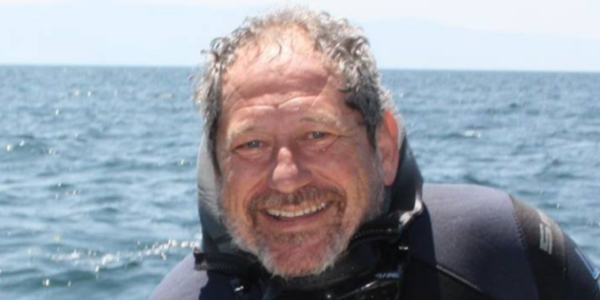

It’s not. “You’re gonna get your rust fix today,” says Mossy, one of the Australian divemaster/instructors aboard Solomon Islands Dive Expeditions’ Taka.

What’s left of an old Japanese fishery wharf now overlooks a graveyard of wrecks. Its dramatic centerpiece is believed to be the bow of USS Minneapolis, which, incredibly, approached Tulagi in November 1942 with that bow dangling, blown open like a tulip in the nearby Battle of Tassafaronga, scattering shells and armaments from open magazines as it limped into port.

With little but palm fronds for air-raid camouflage, its crew and a Seabee unit removed the damaged bow — dropping it in the harbor — and improvised repairs sufficient to sail all the way back to California, where a new bow was attached; Minneapolis served with distinction for the rest of the war and beyond.

Submerging in the murky harbor feels like descending through time. The site includes a landing barge and more recent wrecks of a fishing boat and a tug, piled on one another. Even in the harbor’s low viz, torpedoes and shells — many still live — are outlined below, making what happened here 75 years ago suddenly, vividly real.

A nearby transport, lying on its side on a slope, looms from 60 feet almost to the surface, a massive metal bulwark decorated incongruously with delicate corallimorphs, like doilies on a doomsday machine. It’s hard not to think of the fear — inspired and endured — created by these awesome engines of war. They retain that aura still, of ferocious creatures not dead but only sleeping.

Mention the Solomon Islands to most Americans and you’ll get blank looks. Not many could locate this nearly 1,000-island archipelago in the southwest Pacific region known as Melanesia.

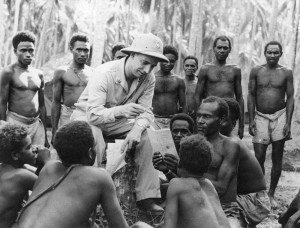

Mention Guadalcanal, and that changes. From August 1942 to February 1943, Americans and their allies fought a bitter land-and-sea campaign here against the Japanese. My grandfather was one of those Americans. In a way I’ve come here looking for him, curious to understand how his wartime experience shaped the man I knew, and to learn how the presence of those troops affected the Solomon Islands and its people.

Today, military tourism — Japanese and Allied — is popular in this emerging destination where wartime wreckage is hauled out of dense jungle practically every day and Quonset huts still dot the main road through the capital, Honiara. The lingering effects of battle also are unmistakable underwater. Ironbottom Sound, between Guadalcanal and the nearby Florida Islands (originally the Nggela Islands), contains more than 50 wartime wrecks, a few of them at depths accessible to tec divers. Cruising between Guadalcanal, the Floridas and Savo Island, the sound seems crazy-small for how much traffic was passing through here 75 years ago — you and your enemy would have been right on top of each other, and every islet could conceal a hostile plane, ship or sub.

Solomon Islanders are proud of the critical part they played alongside Allied forces, mostly as scouts and porters. Open-air museums of salvaged artifacts are lovingly maintained by families who own the lands that house them. Separate, somber memorials to Allied and Japanese forces crown two hills overlooking Honiara and its harbor.

But the imprint of war is only a small and comparatively recent part of the story of the Solomons. Despite that horrific intrusion and the evidence that remains, the cycle of life here seems undisturbed for ages. The underwater offerings are comparable — and perhaps superior — to Indonesia’s Raja Ampat, with the addition of a culture thousands of years in the making that seems to integrate land and sea, part of the natural environment rather than master of it.

In three back-to-back Florida Islands dives that stand out as perhaps the best of my dive career, my logbook notes grow ever more incredulous at the beauty and abundance all around us.

At the first, Mbeasiri Point, northwest of Sandfly Passage between Olevugha and Nggela Sule islands, the map at our 6:30 a.m. briefing is strangely blank — an outline of a point with a 50-meter wall, a shelf at about 10 meters and an “X” in the blue for our drop zone. An exploratory dive! Everyone perks up.

We do a live drop into a pretty good current and, right away, everywhere the eye falls is a beautiful scene: huge elephant ear sponges in soft pastel greens, peach and lavender, and massive, diversize gorgonians — lacy yet substantial — in brilliant greens and gold. There’s every kind of critter and reef fish, including two or three anthias, an angel and a parrot I have never seen before; on the other end of the scale, we spy a massive bumphead parrotfish the size of our divemaster Mike, who’s 6 feet 4 inches tall. A big Maori wrasse cruises by, and then an eagle ray. As the current drops us in a little cove at about 60 feet, here comes another ray — Manta! I think, but it’s too small: devil ray! It makes an artful, swooping pass very close, clearly checking us out, and then a little blacktip reef shark distracts us, its markings sharply contrasting in viz that’s easily 150-plus feet, illuminated by the morning sun. The devil ray must have been a scout — a minute later comes a squadron of eight or nine more, flying in a perfect V formation like geese.

The next site is called Switzer for its huge underwater mountains and meadows, teeming with life. No wonder photographers love these islands: There’s a picture to be made here about every 10 feet. The current gives us a perfect ride past the smorgasbord of life that is the Solomons. We hook in here and there just for fun, to take it all in; so many durgons, fusiliers, anthias — everything that schools is busy doing so, in so many directions it’s dizzying.

We end up high over a gentle slope of acropora in pristine condition, a million little eyes peeking out, colorful small bodies flashing here and there in the protective thicket. Suddenly we see an odd paddle-shaped fish at the surface — it is a paddle, and the outline of a dugout canoe, a common sight in the Solomons, where man is never far from the sea

Nearby Tanavula Point is another stunner — white cliffs above, scooped out like ice cream, swirled with shades of gray and tan, little Seussian lips of greenery barely overhanging all. Below, huge coral fields almost break the surface; a sheer wall goes on and on, with no bottom in sight, and avalanches of anthias give new meaning to the phrase “living color.” As we approach the point, a strong downdraft sends us zipping back the way we had come. We surface in shallows at the top of the wall, startling a villager snorkeling in the washingmachine- like boil at the tip.

We wave, but it’s not easy to interact with shy villagers on scuba. It’s fun to try to follow Taka’s friendly crew speaking to one another in the local pidgin dialect, which has many English influences. We get the chance to really appreciate local culture with a village visit at Olevugha Island, in the western Floridas. As soon as we wade in from the panga I feel the Earth tilt — before me are women adorned with sisal and flowers, nut bells twined around their ankles, who have just stepped out of my grandfather’s photographs as though no time had passed at all. About 100 villagers are assembled, whether for the performance or the novelty of foreign guests isn’t clear. Islanders across Melanesia compete in song and dance teams, we’re told, and these women are regional champions. We don’t need the interpreter’s help to understand a funny dance about a praying mantis, or a sweet lullaby, or a song called “Schooner,” performed by a men’s group on bamboo pan flutes, that evokes European sea chanteys, enfolding elements of invading cultures as the Solomons always have, and still do today.

I didn’t really find my grandfather, who survived the war and a long career in the Army, retiring decades later to begin an unlikely second act as a social worker. But I did hear voices. We moor at a site called White Beach, on the south side of Mbanika, in the Russell Islands, occupied in February 1943 by U.S. troops after Guadalcanal was secured. The action was part of a push west toward New Britain and Rabaul, where my grandfather — then an Army captain attached to the famous “Carlson’s Raiders,” the 2nd Marine Raiders Battalion — would serve before returning to Washington to share what had been learned in the battles around Guadalcanal. To a 21st-century American, the first reaction to a wreckage-strewn site like White Beach is embarrassment: Um, sorry for the mess!

But today that historic devastation is a muck paradise. Sinking slowly in the dawn light, we pick out the remains of a wharf, its jagged pilings piercing the surface; a mighty, upside-down landing barge and a jeep; and a split-open fire extinguisher revealing a tiny nudi. All over the Solomons, when the war ended or campaigns moved on, unneeded materiel was simply pushed off docks and left where it fell. I could almost hear the laughter and feel the presence of relieved young men making a party of these final acts — We’re outta here! — witnessed by myriad beer and Coke bottles still resting on the bottom.

Whether from the gloom or the awe induced by the doomsday machines lying below, I feel a pleasurable frisson as from a rousing ghost story. So many voices speak from the past here, it’s hard to sort them out. The world was changing along with the Allies’ fortune, although no one knew it then — arguably the beginning of the American era, for better or for worse.

Yet at White Beach as all over the Solomons, life — inexorable, unstoppable — takes over from death and destruction. On every surface and in every nook and cranny, life grows, beauty emerges and the great, mysterious cycle revolves anew.

Vilu War Museum About a half-hour’s drive west of Honiara, along a coastal road that did not exist during the war, when all traffic was by boat, you’ll find the Vilu War Museum, a fascinating collection of war machines in varying states of decay, pulled from the jungle and assembled here by locals. (Guadalcanal’s interior still yields such finds with some regularity; any human remains are repatriated to the United States.) The museum offers a self-guided stroll with some explanatory signage and a collection of wartime photos inside a small gatehouse; admission is approximately $12 USD.

WWII 75TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATIONS

On August 7, 1942, Allied forces composed mainly of U.S. Marines landed on Guadalcanal and in the Florida Islands to try to deprive the Japanese of bases that threatened Allied supply and communication routes between the United States, Australia and New Zealand. The Allies also intended to use Guadalcanal and Tulagi as bases to support a campaign to destroy an important Japanese base at Rabaul on New Britain. The Japanese made multiple attempts to recover Guadalcanal, leading to months of major land and sea battles until the Japanese gave up the attempt in February 1943. Nearly half a dozen events in the Solomons will commemorate the anniversary on the weekend of August 4, including the Solomons’ annual Veterans Day on August 7, when ships from the U.S., New Zealand and Australian navies are expected in port at Honiara, the Solomons’ capital. Wreath-laying ceremonies are planned over the wrecks of warships in the infamous Ironbottom Sound, named for the plethora of warships, some divable, that litter its depths. A dawn service is planned at the U.S. war memorial on a hill above Honiara. To learn more about planned anniversary events, go to visitsolomons.com.sb.

Source: Sport Diver