It’s one thing to unbuckle a seat belt. It’s another thing to do it while floating upside down inside a helicopter cabin partially submerged in water.

I learned that lesson quickly on a January afternoon in the training pool at Shell’s Robert Training Center on the North Shore. NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune photographer Chris Granger and I had been invited to participate in one of the company’s water survival trainings, an experience familiar to most who work offshore. We enthusiastically accepted.

On one of my first runs in the helicopter simulator I broke the cardinal rule of underwater escape and unbuckled my seat belt before applying my elbow to the corner of the window next to me. The seat belt keeps you in place so that you can leverage your weight, pop the window out and then unbuckle and swim out of the opening.

Instead, my nerves got the best of me and I left myself floating aimlessly. I hadn’t even gotten to the upside down part of the training yet.

“Slow is smooth and smooth is fast,” repeated Derek Joyner, the lead instructor. “If you take your time and you do things properly the first time, you’re going to get out the first time.”

Whoops. That’s what training is for, right?

All of Shell’s more than 650 offshore employees have undergone this type of water survival instruction, known as helicopter underwater egress training, or HUET. Oil and gas companies use helicopters to get people to platforms hundreds of miles offshore.

Workers — and anyone else going offshore — need to know what to do in the event of a crash or botched landing. In total, roughly 6,000 people, including non-Shell employees like myself, have gone through the training at Robert Training Center over the past four years.

Once you get to Robert Training Center you realize it’s the kind of place where safety measures are front and center, not stuffed away in a desk drawer. The speed limit is an odd 17 miles per hour, so that you notice and remember it, we were later told. Everyone must back into parking spaces to ensure an orderly evacuation just in case. Using acronyms like PFD (personal flotation device) and POB (persons on board) is SOP (standard operating procedure).

I consider myself an adequate swimmer with a healthy appetite for adventure. I’m not a pro hang-glider or anything, but I’m drawn to humility-inducing experiences. Still, I had no idea what to expect after the early morning lecture portion of our training.

Granger and I joined the ranks in a helmet, foam clogs and a standard-issue blue jumpsuit. Our training group of six or so people lined the side of the training pool inside a large, muggy warehouse, for a quick briefing before getting in.

Conditions at the training center’s pool can be changed to simulate arctic conditions or a hurricane. On this day, the giant fan for producing hurricane-force winds sat (thankfully) dormant in one corner and the pool water, we were happy to find, was warmed to about 85 degrees. I hopped through the water awkwardly as I got used to swimming in full clothing for the first time in a while.

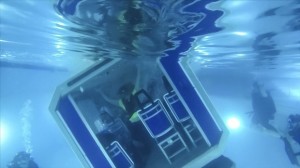

The helicopter simulator is boxy and open on one end, with six seats and different types of windows and hatch doors inside. An expert explained the seats, safety harnesses and windows are similar to what you would find on a Sikorsky S-92 or Leonard AW-139, the helicopters used to move people offshore. Some of the seats sat low to the ground, simulating those with legs that have collapsed on heavy impact, a design feature meant to protect your back.

We practiced bracing for impact, pushing out the helicopter windows and unbuckling the three-point safety harness on land before graduating to a short underwater obstacle course. The training also included basic water survival techniques, like how to make a floatation device with your clothing and how to stave off exposure and signal a passing vessel if your group is stranded in open water.

In all, we did about 10 runs of varying difficulty in the helicopter simulator. An operator stood on the side of the pool using a remote control to lower and flip the simulator in the water.

The most difficult run, at least for me, had us flip upside down underwater, wait for a classmate across the aisle to push out their window and then swim behind them through the window opening. Scuba divers and experienced instructors with goggles were an arms-length away the whole time. Still, the feeling of isolation slipped over me with the water line. My nose burned as we flipped and the water pushed in. I grasped around for an orienting landmark. My heart beat strong as I tried to conserve my movements and my oxygen.

At some point it hits you. This is just a simulation. The water is warm and clear. A scuba team is watching over me. What would an actual emergency look like? How would I actually react?

Speaking after a long day of training, Joyner said the first step is being aware of what to do and what you are capable of. You don’t have to be an offshore worker to get value from the training, he said.

“The procedures for getting out of a body of water would be the same, whether it’s a helicopter or an automobile,” Joyner said.

Here are a few lessons we learned in training how to get out of a helicopter or vehicle submerged in water.

Stay calm.

This is, hands-down, the first and foremost rule to live by in any emergency. It’s also the hardest to follow, especially, as I learned, when water is rising up around you quickly. Joyner noted human nature is to panic and rush our actions, but slow and deliberate movement conserves energy and puts you in a better position to escape.

“The biggest thing in any emergency situation is remaining calm,” Joyner said. “If somebody starts panicking, they’re going to do the wrong thing.”

Wait for the cabin to pressurize.

Whether it’s a helicopter or a vehicle that’s sinking, “at some point you’re going to have a difference in pressurization between the inside and the outside,” Joyner said. You won’t be able to open a door if there’s a wall of water on the outside and none on the inside. During HUET, we practiced waiting for the cabin to fill up with water over our heads before opening the window next to us, then releasing our seat belt and exiting through the opening.

Joyner said cars with electric windows should still have enough power to allow the windows to go down even after a few minutes in water.

Get the window open first, then unbuckle.

Window, buckle, get out. Joyner and the other instructors repeated this over and over. If we had only one takeaway from the training, Joyner said he wanted that sequence to be it. Staying buckled in underwater seems scary, but as I learned, it’s really tough to do anything (like get a window open) when you’re floating. The seat belt helped keep me in place as I worked on getting out of Dodge.

Joyner added it is important to know how to get out of your seat belt and do so naturally and calmly. Take note of how your seat belt works and what you would need to do to get out of it in various situations.

Don’t let a multi-purpose survival tool be a security blanket.

A lot of people get window breakers and other multi-purpose tools to put in their cars, but never take them out of the package before throwing them in the trunk. Make sure you know how the tool works and that it is accessible from the driver’s seat, Joyner said.

“Try going to a junk yard and actually busting out a window. It’s not quite as easy as they make it look on TV,” Joyner said.

Have you taken a HUET course?

What did you think? What surprised you? What did you learn?

Share your experience in the comment section or email reporter Jennifer Larino at jlarino@nola.com.

Source: Nola