Most of us consider vision and hearing to be two separate senses. But dolphins use sound to see, emitting clicks, squawks and whistles to reveal hidden objects. This is called echolocation, and a new map of dolphin brain circuitry hints at how the animals do it.

In a forthcoming paper in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, neuroscientists at Emory University have, for the first time, mapped the sensory and motor systems of two dolphin brains. Unlike most mammals, which process sound in the temporal lobe, the dolphin auditory nerve is wired to both the temporal lobe and the brain’s primary visual region. And that connection could help explain the animals’ fantastic sonar.

“For decades, we’ve thought of the dolphin brain as having one primary auditory region,” said cetacean neuroscientist and study co-author Lori Marino in a press release. “This research shows that the dolphin brain is even more complex than we realized.”

Echolocation—emitting high frequency sounds to navigate and spot prey—is a rare skill found scattered across the animal kingdom, from whales to bats to even some self-taught humans. But dolphins are unmatched in their sonar capabilities, frequently using sound to detect fish hidden in the sand, which they can then pick out by sight.

“Dolphins are the most sophisticated users of biological sonar in the animal kingdom,” Marino said. “They can rapidly move back and forth between their senses of sight and sound.”

But where dolphins get their stellar sonar from has been a bit of a mystery, for the (very logical) reason that studying dolphin brains is a tad logistically challenging. Fortunately for neuroscientists, Emory University happens to house a large collection of cetacean brains donated over the years from animals that stranded and died on North Carolina beaches.

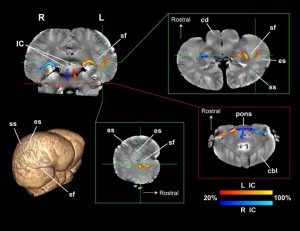

Neural tracks in a dolphin brain revealed used a diffusion tensor imaging (DTI). Image via Gregory Burns / Emory University

In the new study, researchers used a technique called diffusion tension imaging (DTI) to scan the brains of a common dolphin and a pantropical dolphin that washed ashore over ten years ago. Unlike MRI, which shows blood flow patterns in the brain, DTI maps the brain’s wiring structure, offering a much more nuanced view of how sensory information is processed. After 12 hours of scanning each brain, the researchers were able to show that two distinct regions—one typically associated with hearing and another with vision—are clearly connected by the auditory nerve.

As the first-ever images of dolphin brain circuitry, the work raises even more questions. “We studied the brains of two dolphins, which are toothed-whales, and which use echolocation,” lead study author Gregory Berns told me in an email. “Other types of whales, specifically baleen whales (including the largest – the blue whale), do not use echolocation. If we could locate a specimen from one of these whales, we could then determine more precisely which brains regions are for conventional hearing and which for echolocation.”

What’s more, now that a proof-of-concept has been done, Berns is hopeful that DTI might be used to scan all sorts of animal brains housed in museum collections to many questions about how animals think. Who knows, maybe neuroscientists will one day be able to take a preserved brain from a jar, and reconstruct the thought patterns of an extinct organism. Now that’d be something to add to the history books.