Scientists have conclusive evidence that the source of a unique rhythmic sound, recorded for decades in the Southern Ocean and called the “bio-duck,” is the Antarctic minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis). First described and named by submarine personnel in the 1960s who thought it sounded like a robotic duck quack, the bio-duck sound has been recorded at various locations in the Southern Ocean, but its source has remained a mystery — until now.

In February 2013, an international team of researchers deployed acoustic tags on two Antarctic minke whales in Wilhelmina Bay off the western Antarctic Peninsula. These tags were the first acoustic tags successfully deployed on this species. The acoustic analysis of the data, which contained the bio-duck sound, was led by Denise Risch of NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center (NEFSC) and was first published April 23, 2014 in Biology Letters. The research by NEFSC continues and is periodically updated on its website.

Listen to the bio-duck sound.

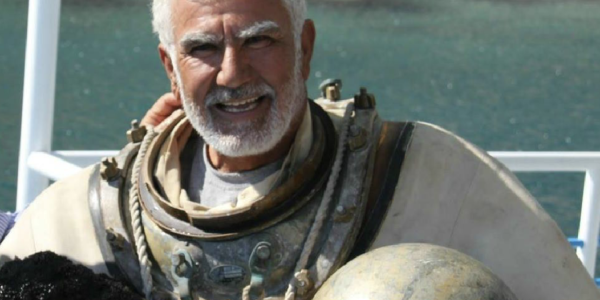

One of two minke whales that researchers from Duke University outfitted with a suction cup tag. The small green tag attached to this whale records depth, heading, and roll, and also has a microphone that records the sounds made by the animal and other sounds in the environment. The suction cup tag detaches after a number of hours, then researchers retrieve the tag to download the data. Recordings made of this and one other animal revealed that minke whales are the source of the mysterious and strange “bio-duck” sound that is common in the Southern Ocean.

Ari S. Friedlaender/Oregon State University

The bio-duck sound is heard mainly during the austral winter in the Southern Ocean around Antarctica and off Australia’s west coast. Described as a series of pulses in a highly repetitive pattern, the bio-duck’s presence in higher and lower latitudes during the winter season also contributed to its mystery. No one knew the minke whales were there. The identification of the Antarctic minke whale as the source of the sound now indicates that some minke whales stay in ice-covered Antarctic waters year-round, while others undertake seasonal migrations to lower latitudes.

“These results have important implications for our understanding of this species,” said Risch, a member of the Passive Acoustics Group at the NEFSC’s Woods Hole Laboratory. “We don’t know very much about this species, but now, using passive acoustic monitoring, we have an opportunity to change that, especially in remote areas of the Antarctic and Southern Ocean.”

The mysterious sounds matched recordings on long-term, bottom-mounted recorders from several other locations in the Antarctic, including the Perennial Acoustic Observatory in the Antarctic Ocean (PALAOA), and near Dumont D’Urville and Ross Island. Germany’s PALAOA is an autonomous observatory with underwater hydrophones, or microphones, located on the Ekström Ice Shelf in western Antarctica. Dumont d’Urville on Petrel Island is the main French scientific research station in Eastern Antarctica.

In the northern Great Barrier Reef of Australia, a swim-with-whales tourism industry has developed based on the June/July migration of dwarf minke whales.

Over the years, Antarctic minke whales have made news headlines as the species hunted and killed by Japanese whalers in the Southern Ocean with the stated goal of scientific research. The new discovery about this same species of whale shows how much we can learn about these animals just by observing them in their environment, say the researchers.

Source: Sport Diver