Charged with looking after a Marine Protected Area twice the size of Great Britain, the isolated South Atlantic island of St Helena takes marine conservation very seriously

By Mark ‘Crowley’ Russell

In 2016, a 448,411 square kilometre Marine Protected Area (MPA) was created around the island of St Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean.

Designated as a Category VI MPA by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), defined as a ‘protected area with sustainable use of natural resources’, St Helena’s MPA extends 200 nautical miles (230 miles or 370km) around the island.

The ensuing Marine Management Plan set three goals in motion: firstly, the island’s marine environment and natural ecosystems are to be protected, conserved, and (where necessary) restored, with appropriate monitoring to track long- and short-term changes.

Secondly, the use of natural resources must be managed sustainably, using evidence-based decisions for the appropriate management of human activities; and thirdly, the importance and management of St Helena’s marine environment must be better understood by both the local and international communities.

Last year, the MPA was adopted by Sylvia Earle’s Mission Blue foundation as a global ‘Hope Spot’, recognising that although the small volcanic island is one of the most remote in the world, it is still one of great importance.

‘By becoming a Hope Spot, St Helena can act as a beacon to the rest of the world,’ said Earle when the designation was awarded. ‘Although geographically isolated, it is deeply ecologically connected to many distant realms, and indeed, other Hope Spots.’

Management of the MPA is through St Helena’s Marine Fisheries and Conservation Department, part of the St Helena Government’s Environment, Natural Resources and Planning portfolio, aided by the UK government’s Blue Belt Programme, a marine conservation initiative aimed specifically at the UK’s Overseas Territories.

Local divers and fishers have been recruited to assist with the MPA’s management, but it’s worth noting the sheer scale of the enterprise with which the islanders are involved.

At 17km long and 10km wide, St Helena’s total land area is just 122 sq km – approximately the same size as Edinburgh – but with a population of around 4,400 people, as opposed to the Scottish city’s half-million souls. At nearly 450,000 sq

km, the island’s MPA is more than twice the size of Great Britain.

A commercial air service to St Helena started in 2017, shrinking the journey time to the island to a six-hour flight from Johannesburg in South Africa, rather than a five-day sea crossing from Cape Town, but the flights bring only a handful of people to an island whose entire population could fit onto a single medium-sized cruise ship.

First discovered by the Portuguese in 1502, and settled by the British in 1659, St Helena was, at one time, one of the most important islands in the world, serving as a shipping post for vessels transiting the southern Atlantic to Europe from India and the Far East.

When the Suez Canal opened in 1869, St Helena’s value to the shipping trade all but vanished, and the island fell into the economic doldrums, but its importance to the South Atlantic Ocean has placed it firmly back on the global stage.

St Helena is located in the centre of the South Atlantic gyre, the ocean current driven by the rotation of the planet which flows in an anti-clockwise direction northwards along the coast of South Africa, west across the equatorial Atlantic and southwards down the eastern coast of South America.

As a result, the waters surrounding St Helena are relatively unproductive, but there are several seamounts within the MPA which – together with St Helena itself – serve as sanctuaries for large amounts of marine biodiversity and staging posts for pelagic fish, especially tuna, the primary catch of the local fisheries.

Fishing from the island has traditionally always been – as the Saints say – ‘one pole, one line, one fish at a time’, a practice now mandated by the rules that govern the management of a Category VI MPA and one which the islanders have had no difficulty accommodating.

Fishing vessels are regularly monitored to ensure compliance with MPA regulations, which has revealed there is very little in the way of transgression by St Helena’s sixteen (as of 2022) registered fishing vessels.

The fishers themselves have been recruited to engage in the science behind ensuring fish stocks remain sustainable. Yellowfin tuna are resident within the MPA for much of the year, with bigeye and skipjack tuna, wahoo, grouper and mackerel all forming part of the catch.

Monitoring of yellowfin tuna stocks was begun in 2015 through a Darwin Plus initiative, and in 2018 a Blue Belt-funded research programme through the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas) was instigated to study the habitat use, movements and retention time of yellowfin and big-eye tuna in the St Helena Exclusive Economic Zone.

Later in 2018, St Helena also began participating in the Atlantic Ocean Tropical Tuna Tagging Programme funded by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tuna (ICAT). This saw more than 5,800 tags deployed across a variety of tuna species, and financial incentives provided to local fishers for gathering data from any tagged tuna they caught.

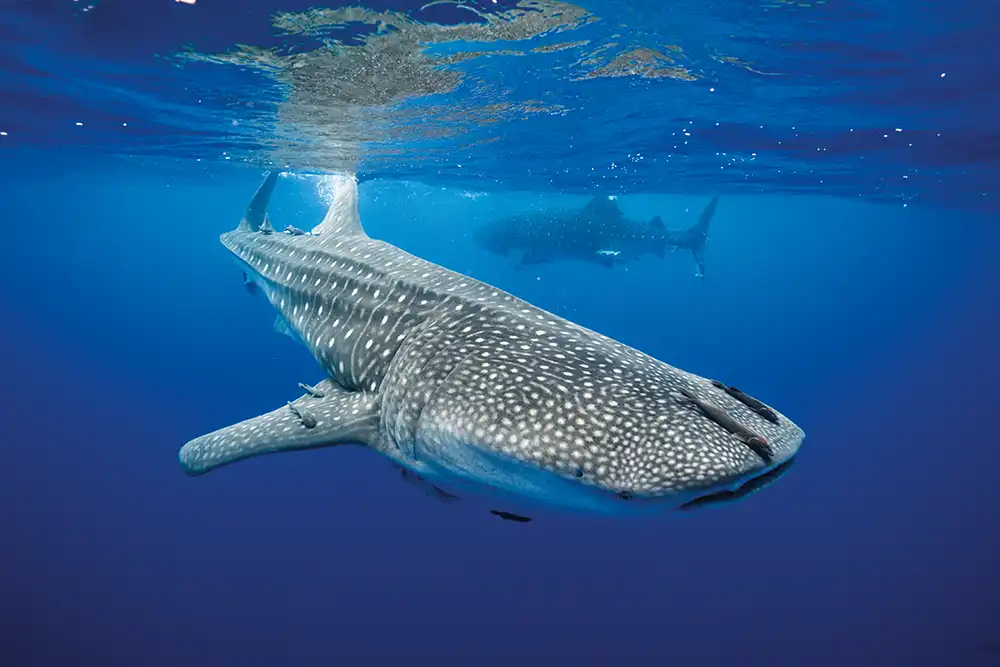

Of the other migratory, pelagic species that pass through St Helena’s waters, the whale shark is probably the most recognisable to divers – and also the most globally significant.

Known locally as the ‘bone shark’ for the ridges that run along the shark’s body, the Saints are highly protective of what has become one of the island’s most valuable marine tourism assets – although it’s possible that tour operators may sometimes wish that local species with a permanent presence were as equally well appreciated.

Whale sharks gather in numbers between December and March each year, with sometimes as many as 30 or more individuals spotted in a single day. The sharks congregate in an almost equal ratio of adult male and female fish, implying strongly that they are gathering around the island to find a mate, or, at least, stopping for some much-needed R & R on their way to their breeding grounds.

Anecdotes of mating behaviour that have been witnessed suggest that the breeding grounds are nearby but to date, there has been no documented evidence, although research continues each year as the sharks appear.

For many scuba divers, swimming with a whale shark is the underwater highlight of their diving lives, and to swim with multiple, fully-grown individuals, a rare and undeniably thrilling event. Even before the planes started flying and the MPA had been signed into effect, however, the Saints had already put rules and regulations in place regarding human interactions with the gentle giants.

Diving with the sharks is forbidden – although it’s obviously not possible to stop them passing by if divers should happen to be in the water at the time – and any operator wishing to pilot boats to swim and snorkel with the animals must undergo training and adhere to the regulations regarding interactions with the sharks.

The measures put in place for whale sharks are just a small part of the work that goes into protecting the MPA, but are a good and easily observable example of the care and attention that the Saints place on their waters, from what is a very small number of available staff.

Nevertheless, much work goes into continuous research within St Helena’s marine environment, which include vastly more than just its whale sharks – even if they are the easiest to spot.

Closer to shore, continuous surveys of the local reefs are performed by divers and have been regularly turning up new discoveries. A total of 829 marine species have so far been recorded within the MPA, 19 of which were reported in a 2019 study as being previously unseen in St Helena’s waters, and three of which were entirely new to science.

There are now at least 18 species known to be endemic to St Helena and found nowhere else in the world, including the St Helena fangtooth moray (Enchelycore sanctaehelenae), St Helena white sea bream (Diplodus helenae), and the quite beautiful St Helena butterflyfish (Chaetodon sanctaehelenae).

Although St Helena is located in a sub-tropical latitude, the cooler water temperatures of the South Atlantic have stymied

the growth of the coral reefs that would be found in other locations. Nevertheless, there are ten species of octocoral found around the island, including two unique to St Helena, the orange cup coral (Balanophyllia helenae) and St Helena

Tree Coral (Sclerhelia hirtella).

Diving around St Helena is year-round, in water that is usually clear, with superb visibility. The diving and other marine tourism activities are now catered for by certified Marine Accredited Operators – most of whom, it has to be said, were abiding by the new guidelines before they were set in place.

The creation of the MPA is a definite boon for marine tourism which, while growing, is still in its relative infancy. The implementation of an MPA at a time when the marine environment remains mostly pristine has significant advantages over similar protections in other countries that, while also worthy of praise, have been put in place long after the damage has already been done.

‘The Ocean has a way of enchanting us, capturing our imagination and intriguing us with mysteries of the unexplored,’ said Helena Bennett, Director of the St Helena National Trust when the island was designated as a Hope Spot.

‘Our island and its surrounding waters are steeped in our culture and traditions and have played a massive role in our history, evolving our way with a sense of nostalgia and a feeling of belonging and home.’

For more on St Helena, check out our DIVE Guide to St Helena. Year-round dive trips to the island are available from Dive WorldWide.

The post An Island of Hope – St Helena’s extensive MPA appeared first on DIVE Magazine.